People — including citizens outside of Indiana — are watching how Indiana treats its state forests. An astute Ohio resident took the time to write to Indiana’s governor, and shared her letter with IFA. Her message reinforces the fact that we in Indiana need to remain vigilant and vocal in stating our desires for our taxpayer-owned forests. Her ideas also show that we have significant untapped potential among our Indiana forests left standing.

Dear Governor Holcomb,

As an Ohio resident, I am writing on behalf of the mature forests located throughout Indiana’s State Forests. Our family has had the pleasure of visiting many of these forests during our vacations. Several years ago, our family had to relocate for my husband’s job. We moved from our wooded property in Southeast Ohio to the cornfields of Iowa. We missed the forested ecosystem of Ohio and Indiana very much. On our way home we often stopped by Salamonie River State Forest. Those trees, trails, and waterfalls were a welcome sight.

We were saddened to learn that logging may be harvesting many of the mature trees in Indiana’s State Forests. This is especially true of Salamonie River State Forest. The trees that are being culled as “inferior” species are indeed very valuable trees for an ecosystem. The American Beech is habitat for many bird species and the hornbeams are second only to our dying ash for their strength and hardness.

My doctorate work on non-timber forest products allowed me to see the value in an intact ecosystem. I can tell you that once logging takes place, no matter how careful the process might be, the forest is never the same. To believe that we can cut out certain tree species and the native hardwoods will magically reappear is naive.

Invasive species and climate change will prevent the return to forests structures of yesterday. We need to protect these forests for the valuable intact ecosystems that they provide.

In 2008, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated that U.S. forests absorb 792 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. This is equivalent to 11% of all the greenhouse gas emissions from industrial sources. However, in a time when we should be planting trees and conserving existing mature forests, this country is logging at an unprecedented rate.

In 2008, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated that U.S. forests absorb 792 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. This is equivalent to 11% of all the greenhouse gas emissions from industrial sources. However, in a time when we should be planting trees and conserving existing mature forests, this country is logging at an unprecedented rate.

According to the World Resource Institute, less than 1% of large contiguous virgin forests with all species intact still exist in the lower 48 states. Additionally, our forests are extremely fragmented and suffer from droughts and invasive species.

We need to recognize that forests are more than timber and to incorporate them into our climate change planning. Over two thirds of our fresh water supply filters through forest ecosystems. Forests act as a natural flood control. Forests provide habitat for species and help preserve biodiversity. Millions of people flock to national and state parks and forests every year for recreation, hunting, and inspiration.

Although 99% of our virgin forests are gone, we still have forested areas that could be used to sequester carbon dioxide emissions. Studies are showing that mature trees and their ecosystems can store and absorb more carbon than a young forest. Several countries are using this principle to save mature trees and encourage planting of new trees. Using trees to counteract atmospheric carbon also provides an economic benefit. This is achieved via a new program called carbon offsetting.

According to the World Resource Institute, a forest carbon offset is a metric ton of carbon dioxide emissions which is avoided or newly sequestered and is purchased by greenhouse gas emitters as a cost-control mechanism to compensate for emissions occurring elsewhere.

So basically what happens is a company will pay a forest landowner to not log his or her trees, but keep them growing. The growing trees will theoretically be absorbing the carbon dioxide that the company has emitted. It is a win-win situation as the forest remains intact and is able to provide all the services like flood control, and the company is able to offset some of its carbon pollution.

This program is similar to cap and trade in that carbon credits are traded via a carbon market but unlike cap and trade, forest owners, not companies are given the credits. The United States has just recently begun exploring this idea and several new programs are underway. There are four programs that are currently working with southern forest owners in the U.S. to design and leverage carbon credits systems. They are: The Gold Standard, Verified Carbon Standard, Climate Action Reserve, and American Carbon Registry.

In 2014, the city of Astoria, Oregon was faced with a budget crisis. One of its options to raise revenues was to aggressively timber old growth hemlock in the Bear Creek Watershed. However, the city decided to enter into an agreement partnering with a non-profit organization, the Climate Trust.

The 3,423 acre watershed would be used to offset greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fueled power plants in the state. The program will sequester carbon dioxide in growing trees for forty years. The first year will earn the city $358,750 in carbon credits. Following years will add $130,000 annually to the budget for the next nine years. By the end of the agreement timeframe, the city will have gained $2 million in revenues after fees.

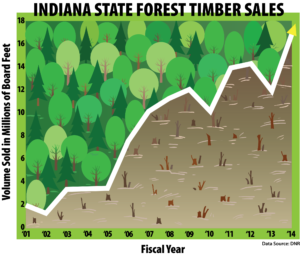

Hopefully, these carbon credit programs will start to become viable options in Indiana as well as other states especially since there has been a 400% increase in commercial logging in public forests in Indiana since 2002.

Instead of cutting down more forests, we could be preserving and planting our way out of the climate crisis we now find ourselves in. We need to be innovative and smart because once a tree is cut, it will take decades to re-grow the potential carbon sink it once was.

Additionally, for many people who do not have access to forests, these areas are a place to escape into a world of beauty and tranquility. They are a place to observe the natural world. They are a place to take children and teach science concepts. They are a place to find peace.

I urge you to find another way to make revenue and to allow the old trees to do what they do best, grow and inspire us.

Sincerely, Randi Pokladnik, Ph.D. (Environmental Studies) | Uhrichsville, Ohio