(a version of this letter was published in the Brown County Democrat, 1/16/18)

By Linda Baden, Friends of Yellowwood

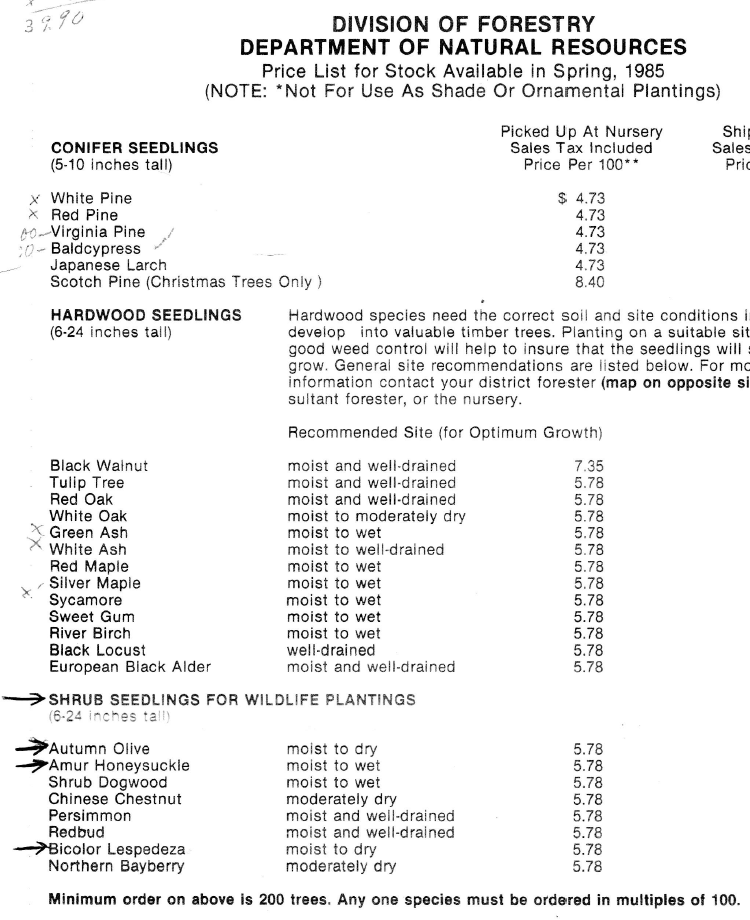

My husband Charlie Cole and I bought our place, an island of private land within Yellowwood State Forest, in the early 1980s. We were eager to begin the healing on an old homestead that had been subjected to the classic Brown County triad of the previous 150 years: over-farming, over-logging, and neglect. So, the first thing we did was to order seedlings from the Indiana Division of Forestry’s Nursery. For the area under the power line, we selected several Shrub Seedlings for Wildlife Plantings, reasoning that we could benefit wildlife and at the same time establish some shrubbery on this bald spot on the land.

An order form I saved from 1985 from the Division of Forestry Nursery (see image below) lists this selection of shrub seedlings. It includes two plants-Autumn Olive and Amur Honeysuckle-that we now know are pernicious invasives of our native hardwood forests. A third shrub, lespedeza, is considered moderately invasive.

An order form I saved from 1985 from the Division of Forestry Nursery (see image below) lists this selection of shrub seedlings. It includes two plants-Autumn Olive and Amur Honeysuckle-that we now know are pernicious invasives of our native hardwood forests. A third shrub, lespedeza, is considered moderately invasive.

Thus, with the most earnest of intentions, and with the endorsement and best advice of the Division of Forestry, we infected our place with two shrubs that we’ve been battling ever since.

But we were not alone: the Division of Forestry itself planted one of these shrubs in Yellowwood State Forest, taking their own advice that Autumn Olive provides wildlife food and cover; interplant with hardwoods to improve soil (quoting from a 1987 Forestry Nursery order form).

You see, in the 1980s, IDNR Foresters knew that Autumn Olive alters nutrient cycling by adding nitrogen to the soil, but they didn’t yet realize that this encourages other invasions. Beyond this, the problem with Autumn Olive, according to the Indiana Nature Conservancy, is that it out-competes and displaces native plants by creating a dense shade that hinders the growth of plants that need lots of sun. It can produce up to 200,000 seeds each year, and can spread over a variety of habitats as its nitrogen-fixing root nodules allows the plant to grow in even the most unfavorable soils. Not to mention that it reproduces quickly and with little effort at all.

In the mid-1990s, the Division introduced Callery Pear as a fast growing wildlife shrub; small pear provides food for birds in winter. Fast-growing indeed! We now regard Callery Pear (also known as Bradford Pear) as a “Bad, Bad Plant with Pretty Flowers,” which is the title of a 2013 alert on the Monroe County Identify and Reduce Invasive Species website that describes the invasion of Callery Pears on 900 acres of forestland in Martin County.

In the mid-1990s, the Division introduced Callery Pear as a fast growing wildlife shrub; small pear provides food for birds in winter. Fast-growing indeed! We now regard Callery Pear (also known as Bradford Pear) as a “Bad, Bad Plant with Pretty Flowers,” which is the title of a 2013 alert on the Monroe County Identify and Reduce Invasive Species website that describes the invasion of Callery Pears on 900 acres of forestland in Martin County.

Truth is, we don’t always know what we don’t know even if we are well-trained and well-intentioned scientists or foresters. The Division made its recommendations based on what they knew at the time. Unfortunately for our forests, we are continuing to pay the price for these good intentions.

Which brings me to my point: by relying so heavily on what they take as management gospel to the exclusion of any other approach, the Division is endangering the ability of our already embattled hardwood forests to withstand future threats, foreseen and unforeseen. We need to embrace those unknowns by balancing harvested with unharvested areas of the state forests, just in case what we think we know turns out to be not what we expected.